The Art of Searching Earth

BBC's Aliaume Leroy on OSINT inspirations, geolocation, and Anatomy of a Killing

“Geolocation” is basically a combination of Googling the earth and Google Earth.

While there is certainly an element of plain luck to locating an image, like if an identical picture happens to be geotagged on Google, there’s a community of open source journalists that view geolocation, searching the earth, as an artform.

They train for hours, practicing with pictures on Twitter and @quiztime, because geolocation is a learnable skill. It’s a trainable mindset, a different way of looking at the online world.

It’s also an invaluable asset for any fact checker, to be able to expose fake and repurposed photos.

Practitioners of geolocation train again and again with mundane pictures, honing their eyes for the real deal, the nights when we wake up to truly horrific headlines (like this weekend in Myanmar when “Over 100 killed in deadliest day since Military Coup”) and investigative journalists are tasked with piecing together “which village,” “which street,” and “where exactly.”

One journalist who has spent years perfecting the art of searching earth is French investigator Aliaume Leroy. I recently had the fortune of working with Leroy, who is currently a producer at the BBC Africa Eye, and by all means an incredible OSINT investigator, trainer, and mentor. On this issue of Brackets, Leroy has generously agreed to share some of his investigative wisdom and geolocation techniques!

Cameroon

In 2018, Leroy, alongside many other journalists, woke up to find a truly horrific video on Twitter, one that captured the world’s attention. The viral video, which showed two young women, and children being executed by men in army uniforms, had no context behind it, not even a country.

Soon after, an Avengers like open source team assembled to uncover the origins of the video. Leading the efforts was Leroy, alongside several other superstar investigators including BBC’s Ben Strick, NYT’s Christiaan Triebert, and Bellingcat’s Youri van der Weide.

Leroy’s team geolocated the video. They identified a village in Cameroon based on a matching mountain background on Google Earth. “Every detail could be key in geolocation”, Leroy tells me, including details of mountain ranges, natural formations, trees, buildings, signs, and roads.

“When we got the geolocation, everyone wanted to tweet it,” Leroy says. “It was tough to hold off [on tweeting], but everyone had a conversation, and agreed that we could go further. We could potentially find who the men were, and what was happening.”

For Leroy, this act of holding off on tweeting was a symbolic moment, when “OSINT” evolved into investigative journalism. Soon after, the team identified the perpetrators of the killings as a unit of the Cameroon special forces.

As a result of their investigations, the soldiers were prosecuted, and a Peabody winning BBC Africa Eye documentary Anatomy of a Killing was produced. To this day Anatomy of a Killing remains one of the most iconic examples of open source investigations, that certainly put geolocation on the map.

Paris, Montreal, London

Before we talk more about searching earth, let’s talk about where on earth Leroy is from! The first clue — a beautiful Parisian backdrop emerges whenever Leroy opens his window on a zoom call.

His French background adds a language asset to the team for investigations in Francophone Africa. Leroy’s international connection also extends to Canada! having obtained his undergraduate degree at the University of McGill in Montreal, known colloquially by some as the “Harvard of the North.”

In his senior year at McGill, Leroy had his first foray into open source investigations, where in his Economics 316 course, the Underground Economy, he authored a paper on Arms Trafficking.

In December 2014, his investigation into arms trafficking was also published on the then emerging open source collective Bellingcat.

After Montreal, Leroy completed a Masters degree at King’s College London. There, he met a fated friend and future colleague. In the same Master’s program was Christiaan Triebert, the New York Times visual investigator profiled in the first issue of Brackets.

Together, the two graduated from King’s College and continued collaborating on Bellingcat investigations. Leroy also started at Global Witness focusing on open source work on natural resources and conflicts, and was later recruited into the BBC Africa Eye.

* Want to read more about OSINT superstars? You can find my feature on Triebert here!

ExampleTown, USA

Next, let’s go through an actual example of geolocation in action.

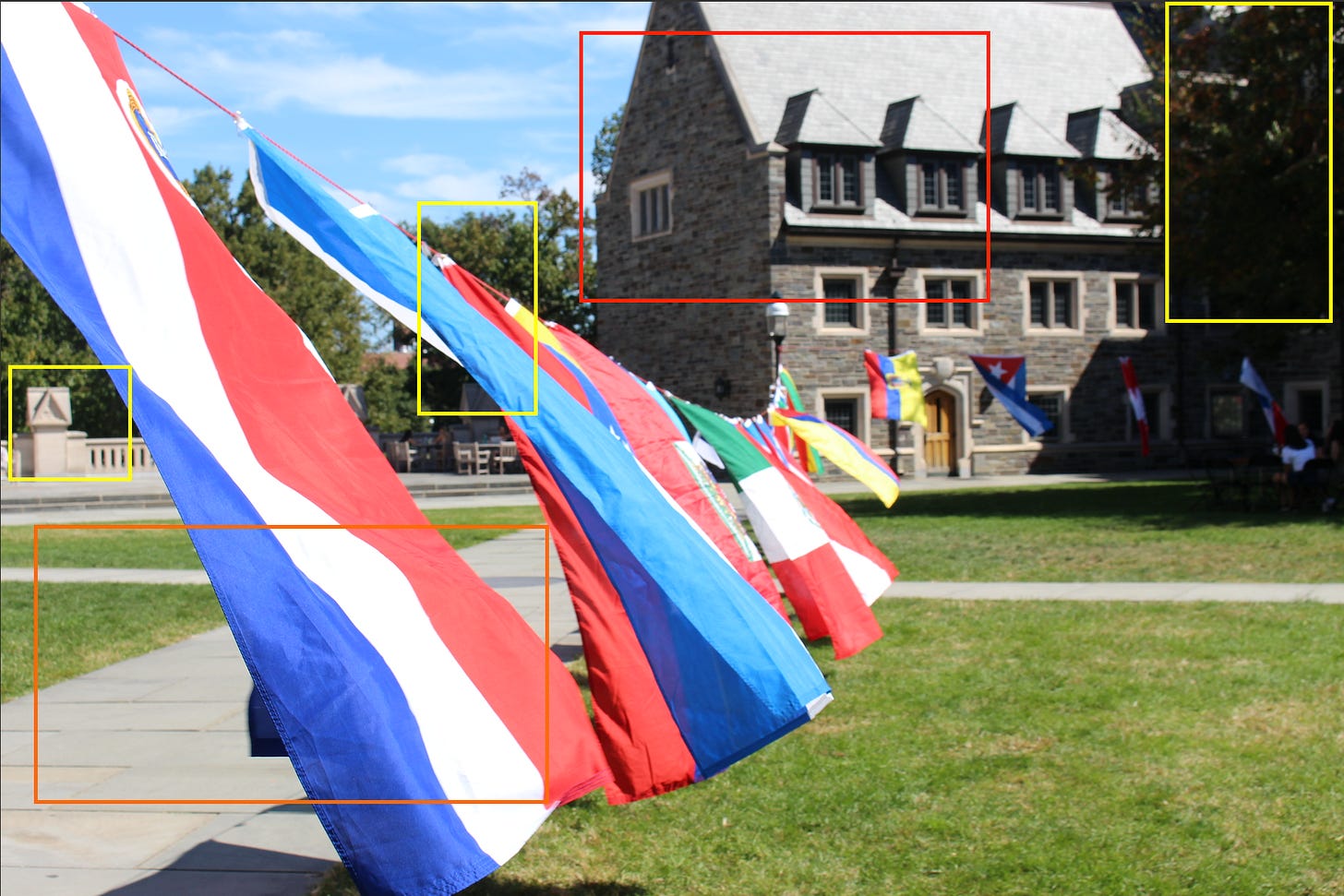

The example I chose is a photo from the United States. Its difficulty is relatively easy, as a wide range of satellite imagery is readily available for North America, that may not be available in Latin America or Africa.

a) Search Radius

The first step is to find as much as possible about the image online.

You may notice that this looks like a college town. You may even uncover on Twitter, that this is actually a photo I took for international orientation at Princeton! The home run, of course, is to find an actual geotagged copy of the image somewhere like on Google Maps.

Regardless of what you uncover, anything you find helps inform a search radius, an area where this image could be from. If someone in a video of a warcrime in Cameroon says that “this village is close to town, even closer than the airport” then voilà you have a search radius. If someone comments a university name on a social media post, or a campus tour guide posts a similar photo, then voilà you have a search radius (in this case the Princeton University campus).

Leroy recommends actually drawing out your search radius on Google Earth, which you can do easily with the ruler tool.

b) Mid-game, Pinpointing Your Suspects

Once you’ve established an area of search, you can dive into Google Earth for potential matches. In this case, we notice that the crosswalk on the lawn makes a noticeable X shape. So for flagging potential matches, we look for all the X shape cross walks, next to a building within our search radius.

Leroy’s advice is to cast a wide net at first. Our point of view is distorted between photos and satellite imagery; so even things that don’t look like a match at first, could still be a good match.

c) End-game, Making the Match

The last step is to go through the potential matches on Google Earth, and identify geographical features, trees, buildings, crossroads, landmarks, and details to help verify our photo.

Looking through Google Earth, one of our flagged locations matches with the photo of interest! The geocode is Lat: 40°20'37.60"N; Long: 74°39'29.23"W.

Planet Earth

One of Leroy’s personal geolocation highlights was investigating the death of Oscar Perez, the leader of the National Equilibrium Movement in Venezuela, in collaboration with Bellingcat’s Giancarlo Fiorella.

⌛️ “We are going to surrender! Stop shooting!”: Reconstructing Óscar Pérez’s Last Hours

In reconstructing Oscar Perez’s last moments, Leroy had to purchase additional satellite imagery. The buildings near Perez’s Venezuelan safe house changed often, so they needed more recent imagery than what was available on Google Earth.

The lesson here is that even Google Earth is limited. The best investigators are not limited to a single tool, and are able to pivot to other resources. In investigating more isolated and rural areas on earth, we may also need to access a variety of sources, both from for purchase imagery on sites like Sentinel Hub, and free crowdsourced maps like Wikimapia, OpenstreetMaps, and KartaView.

Here are some more great mapping resources for geolocation:

Bonus tip from Leroy: install these awesome Google Earth plugins that allows you to overlay map layers from other sources!

Thanks for reading this issue! If you’re interested in learning more about geolocation and OSINT, Leroy also founded a non-profit, Open Facto, a platform for French open source investigators, with great resources and case studies, that is definitely worth checking out!

With work ramping up, I’ll be reducing the volume of Brackets, to 1-2 issues a month. I’ll still be making posts on Wednesdays, and have some exciting content planned, both on product reviews and more profiles of amazing investigators. Thanks again for your continued support of Brackets, and until next time!